Expert View by Asher Goldman

Imagine, for a moment, that we’ve invented a new device. Maybe it’s a bit like a catalytic converter: you put it in your car’s tailpipe and, boom, it reduces the volume of carbon emissions from your vehicle. Amazingly, the device gets better with age, wringing out more and more emissions each year. And crucially, the device is cheap, proven, and ready to be adopted at scale. Although the device doesn’t exist, California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is a policy that delivers these outcomes.

The LCFS program is simple at its core: low-carbon fuels receive tradeable credits and high-carbon fuels receive deficits. Deficits are offset by credits and companies are not allowed to end the year with deficits. The volume of credits or deficits a fuel creates is a product of its carbon intensity – the carbon emissions produced over the lifecycle of producing, transporting, and using that fuel. The program grows stricter over time to ensure the continued ramp up of decarbonization efforts: each year, high-carbon fuels produce more deficits and low-carbon fuels produce fewer credits.

The intended flexibility and stability of the program structure was designed to encourage investors, project developers, and fleet operators to make long-term investments in their desired decarbonization technology – from EV chargers to biofuels – without fearing policy changes each year. Another important attribute of the policy structure is that the cost of the program is not shouldered by taxpayers, but the producers of high carbon fuels. The LCFS program has helped Generate deploy sustainable technologies, primarily renewable natural gas, necessary for the infrastructure transition.

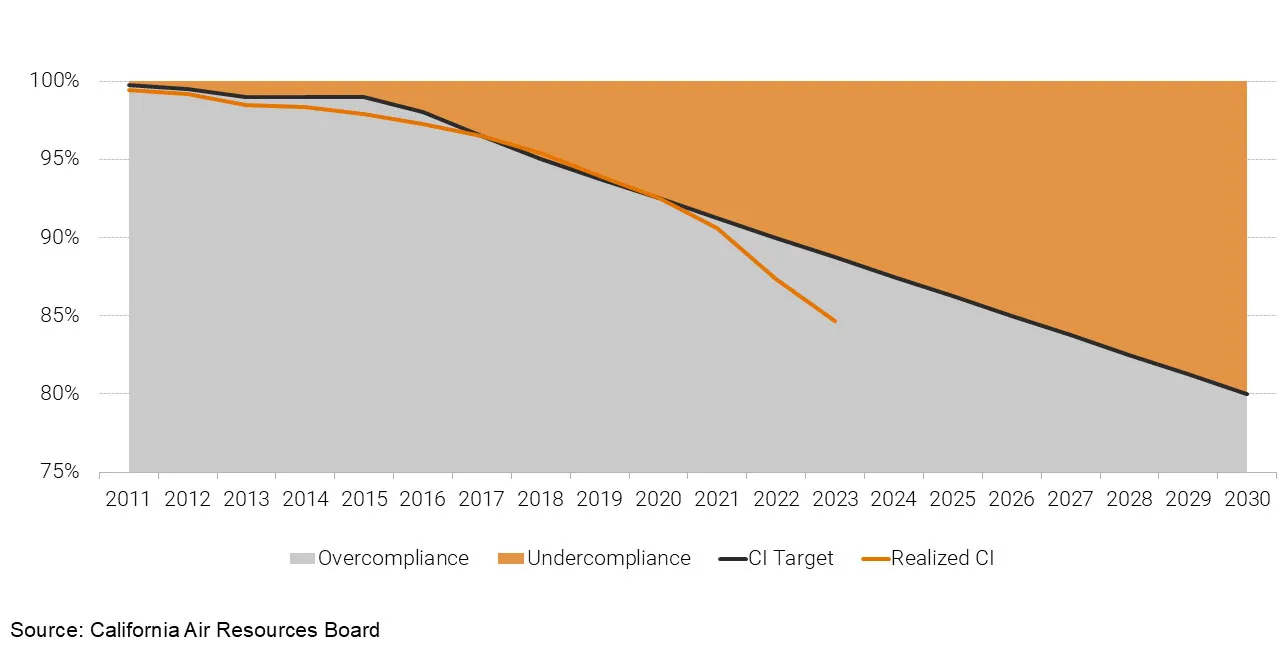

Carbon Intensity Targets for California’s LCFS Program, as of August 2024

Carbon Intensity Targets for California’s LCFS Program, as of August 2024

Since the program’s inception in 2011, California has decarbonized its transportation sector at a quicker pace, lower cost, and to a greater extent than any other US state. It also exceeded the state’s own projections: by the end of 2023, the carbon intensity of California’s transportation sector had decreased 15.3% since 2010 – already surpassing California’s goal for 2026.

While the LCFS program has had a huge impact, its design is not perfect. From 2018 through 2021, the program incentivized billions of dollars of private investment into low-carbon fuel production. Unfortunately, that success challenged the program’s design by causing an oversupply of credits in the market and tanking the price of credits. When credits are cheap, it’s harder to build and borrow against them. At present, very few companies are building new projects to serve the California market as the economic incentive has fallen away. The regulatory body that oversees the LCFS policy – the California Air Resources Board (CARB) – has been amending the policy over the last four years in part to fix this problem.

There are three tweaks to the policy that will help achieve this goal and maintain the LCFS regime as a critical market creator for decarbonization technologies:

The program is also not without its critics. A recent Politico article was headlined, “Everybody hates the LCFS.” It inspires ire from both large emitters and many progressive groups. It’s often said a good compromise is when both parties are dissatisfied and that is certainly true of the LCFS. California has created a markedly impactful program that has done what few if any climate policies have ever accomplished: being ahead of schedule. It has inspired, at time of writing, four LCFS programs in other states with another seven under consideration. California should now make the necessary updates to its program that would allow it to spearhead the next phase of decarbonization.